An Introduction to Web-scraping using Python

Web-scraping is an important technique, frequently employed in a lot of different contexts, especially data science and data mining. It can also contribute as a part of an automation pipeline. Python is considered the go-to language for web-scraping, the reason being the batteries-included nature of Python; you can create a simple scraping script in about 15 minutes and under 100 lines of code. So regardless of usage, web-scraping is a skill that every Python programmer must have under his belt.

Before we start getting hands-on, we should step back and consider what is web-scraping, when should we use it and when to avoid using it. As you already know, web-scraping is a technique employed to automatically extract data from websites. What’s important to understand is, web-scraping is a somewhat crude technique to extract data. If the developers of a website are generous enough to provide an API to extract data, that would be a lot more stable and robust way to do it. So, rule of thumb, if a website provides an API to programmatically retrieve their data, use that. If an API is not available, only then use web-scraping. With that being clear, let’s jump right into the tutorial.

For this tutorial, we’re going to scrape http://quotes.toscrape.com/, a site that lists famous quotes by renowned authors.

The pipeline

We can understand web-scraping as a pipeline containing 3 components

- Downloading. Downloading the HTML web-page

- Parsing. Parsing the HTML and retrieving data we’re interested in

- Storing. Storing the retrieved data in our local machine in a specific format

Downloading HTML

It only seems logical that to extract any data from a web-page, we first have to download it. There are two ways we can go about doing this:

-

Using browser automation libraries like Selenium.

Selenium lets you open a browser, let’s say Chrome, and control it however you want. You can open the web-page in a browser and then get the HTML code of that page, all automated using Selenium. However, this method has a huge drawback — it is significantly slower. The reason being the overhead of running the browser and rendering the HTML in the browser. This is why we should always prefer the 2nd method, resorting to this method in exceptional cases — cases where the content we want to scrape gets loaded by some JS code in the browser. -

Using HTTP libraries, such as Requests or Urllib.

HTTP libraries let you send the exact HTTP request you want to make and get the response, bypassing the need to open any browser at all, unlike the first method. This method should always be preferred, as it is way faster than Selenium. As I already said, we should only employ Selenium when it is absolutely necessary, i.e. when the required data is not there in the initial HTML at all, it gets loaded by some JS code in the browser.

Now let me show you how can we achieve this component of the pipeline using Selenium and Requests.

Using Requests

import requests

result = requests.get('http://quotes.toscrape.com/')

page = result.text

Here, a GET request is made to the URL, which is almost synonymous to downloading the webpage. Then, we can get the HTML source of the page by accessing the result object returned by the requests.get() method.

Using Selenium

from selenium import webdriver

driver = webdriver.Chrome()

driver.get('http://quotes.toscrape.com/')

page = driver.page_source

Here, we first start by creating a webdriver object, which represents the browser. Doing this will start the browser on the computer running the code. Then, by calling the get method of the webdriver object, we can open an URL. And finally, get the source code by accessing the page_source property of the webdriver object.

In both the cases, the HTML source of the URL is stored in the page variable as a string.

Parsing HTML and extracting data

Without getting into theoretical computer science, we can define parsing as the process of analyzing a string so that we can understand its contents and thus access data within it easily. In Python, there are two libraries that help us with Parsing HTML, BeautifulSoup and Lxml. Lxml is a more lower-level framework than BeautifulSoup, and we can use Lxml as a backend in BeautifulSoup, so for simple HTML parsing purposes, BeautifulSoup would be the preferred library.

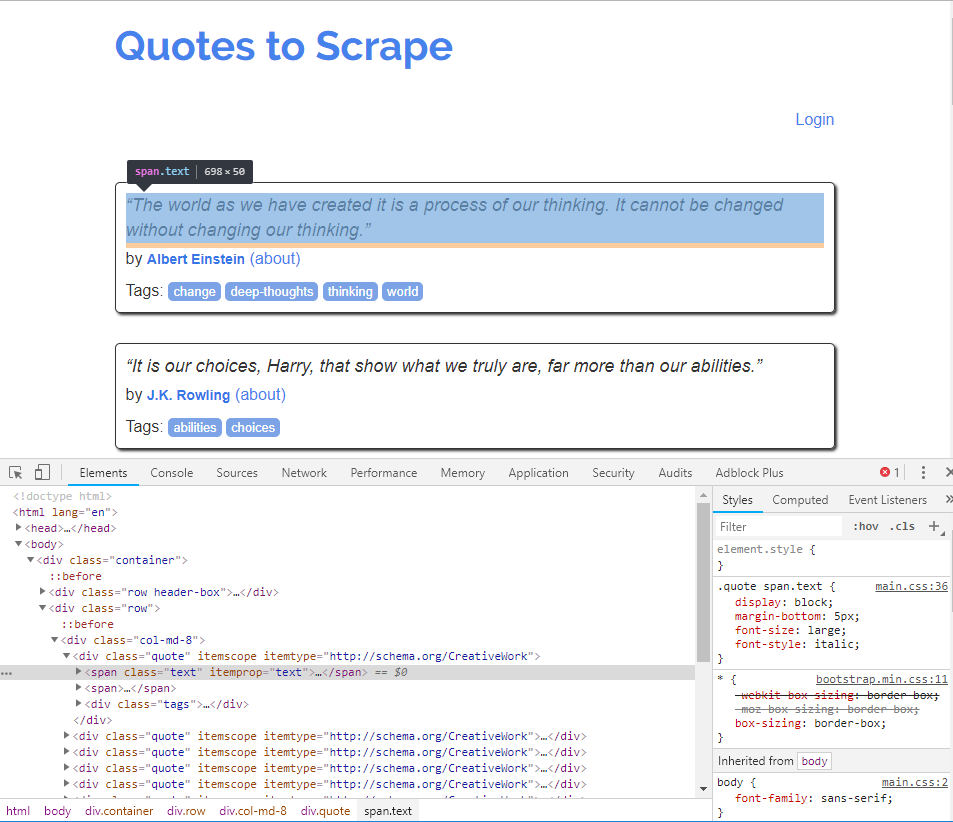

But before we dive into parsing, we have to analyze the web-page’s HTML and see how the data we want to scrape is structured and located. Only when we’re armed with that information, we can get the information we want from the parsed HTML. But thankfully, we won’t have to open the source code in an editor and manually understand and correlate each HTML element with the corresponding element in the rendered page. Most browsers offer a Inspector, which enables us to quickly look at the HTML code of any element just by clicking on them.

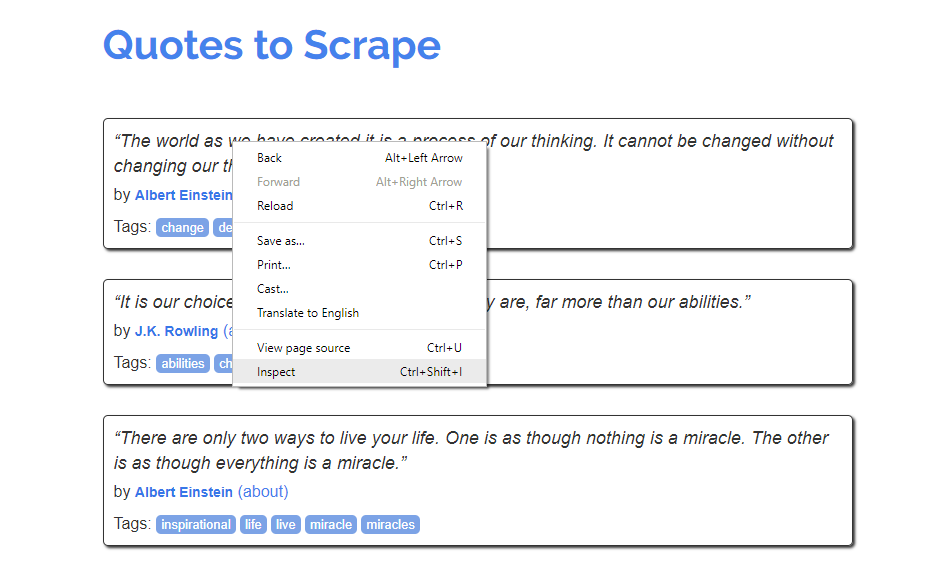

To do this in Chrome, open the web page in Chrome, then right-click on the data you want to scrape and select Inspect. In Firefox, this option is called Inspect Element. Same thing, different name.

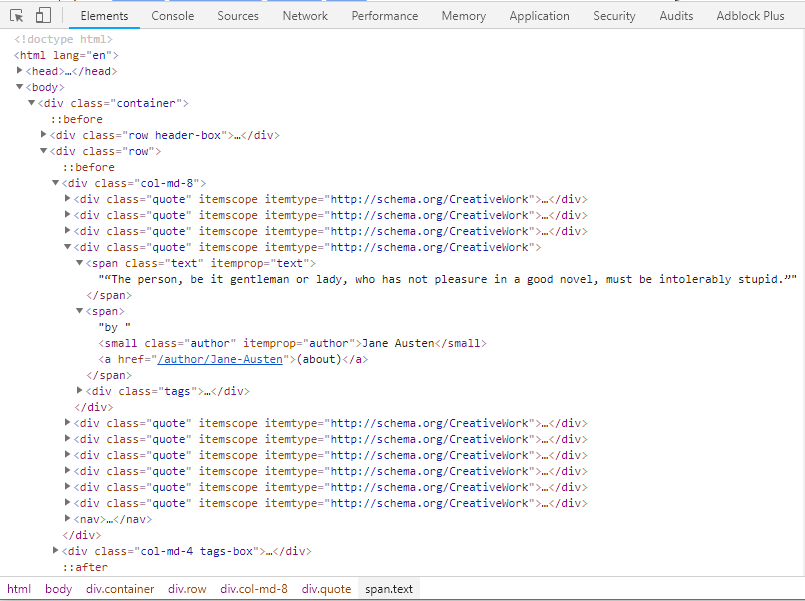

You’ll notice a pane opened at the bottom of the Chrome window, containing the source code of the element you clicked on. Browse through the source code a bit to get an idea of how the data which we want to scrape is structured.

As you can understand after a little bit of inspection, each quote is contained in a div with class="quote". Within that div, the text of the quote is in a span with class="text" and the author’s name is in a small with class="author". This info will be required in when we get to actually parsing the HTML.

Now, let’s start parsing the HTML page using BeautifulSoup.

from bs4 import BeautifulSoup

soup = BeautifulSoup(page, 'html.parser')

First of all, we create a parsed version of the page by passing it to the BeautifulSoup class constructor. As you can see, we also pass a second argument to the constructor, html.parser. That is the name of the parser BS4 is going to use to parse the string you passed to it. You could’ve also used the parser lxml, which we previously talked about, given that you have Lxml installed.

quotes = soup.find_all('div', class_='quote')

Then, we extract all the div tags in the page containing class="quote", as we know those are the divs containing quotes. To do this, BS4 offers a find_all function. We passed the tag name and the class name to the find_all function, and it returned all the tags satisfying the conditions, i.e. the tags containing our quotes.

An important thing to note here is, we’re working with tree structures here, soup and also each element of quotes are trees. In a way, the elements of quotes are parts of the larger soup tree. Anyway, without drifting off into a different discussion, let’s carry on.

scraped = []

for quote in quotes:

text = quote.find('span', class_='text').text

author = quote.find('small', class_='author').text

scraped.append([text, author])

Now, we know that the text of the quote is in a span with class="text" and the author is in a small with class="author". To extract them from the quote elements, we again employ a similar function, find. This takes same arguments and functions almost the same as of find_all, the only difference being it returns the first tag satisfying the conditions, whereas find_all returned a list of tags. Also, we want to access the text property of the returned object, which contains the text enclosed within that tag.

So, as you can see in the code, we loop through all the elements of the list quotes, and extract the quote text and author name, storing them as a list of lists with the name scraped. Pretty printing scraped results in the following

[['“The world as we have created it is a process of our thinking. It cannot be '

'changed without changing our thinking.”',

'Albert Einstein'],

['“It is our choices, Harry, that show what we truly are, far more than our '

'abilities.”',

'J.K. Rowling'],

['“There are only two ways to live your life. One is as though nothing is a '

'miracle. The other is as though everything is a miracle.”',

'Albert Einstein'],

['“The person, be it gentleman or lady, who has not pleasure in a good novel, '

'must be intolerably stupid.”',

'Jane Austen'],

["“Imperfection is beauty, madness is genius and it's better to be absolutely "

'ridiculous than absolutely boring.”',

'Marilyn Monroe'],

['“Try not to become a man of success. Rather become a man of value.”',

'Albert Einstein'],

['“It is better to be hated for what you are than to be loved for what you '

'are not.”',

'André Gide'],

["“I have not failed. I've just found 10,000 ways that won't work.”",

'Thomas A. Edison'],

["“A woman is like a tea bag; you never know how strong it is until it's in "

'hot water.”',

'Eleanor Roosevelt'],

['“A day without sunshine is like, you know, night.”', 'Steve Martin']]

Storing the retrieved data

Once we have acquired the data, we can store it in whatever format we want; CSV file, SQL database or NoSQL database. To be strict, this step shouldn’t count as a part of the scraping process, but still, I’ll cover it briefly for the sake of completeness. I’d say the most popular way of storing scraped data is storing them as CSV spreadsheets, so I’ll show you how to do just that, very briefly. I won’t go into the details, for that you should refer to the official Python documentation. So without further ado, let’s jump into the code.

import csv

with open('quotes.csv', 'w') as csv_file:

writer = csv.writer(csv_file, delimiter=',')

for quote in scraped:

writer.writerow(quote)

As we can see, the code is pretty self-explanatory. We are creating a CSV writer object from the opened quotes.csv file, and then writing the quotes one by one using the writerow function. As it’s evident, the writerow function accepts a list as input and then writes that to the CSV as a row, pretty straightforward.

Conclusion and next steps

This tutorial should help you understand what scraping is basically about while learning to implement a simple scraper yourself. This kind of scraper should suffice for simple automation or small-scale data retriever. But if you want to extract large amounts of data efficiently, you should look into scraping frameworks, especially Scrapy. It’ll help you write very fast, efficient scrapers using a few lines of code. Whatever framework you use, underneath that shiny surface that framework is also using these very basic scraping principles, so understanding this tutorial should help you build the foundational knowledge for your scraping adventures.